People are flocking to South Carolina. The state’s population soared by 7.4 percent between 2010 and 2020 census, and by 2021 it was the nation’s fifth-fastest growing state.

In that ten-year cycle, twenty-five communities in the state saw population increases of more than 40 percent. The population of Greenville, the state’s sixth largest city, grew by 27.9 percent. Nearly 76,000 now call the city home, an increase of nearly 20,000 since 2020.

The swift population rise adds additional stress to the city’s infrastructure. Fortunately, community leaders saw the need to improve its wastewater infrastructure as far back as fifteen years ago. After years of planning, construction on a 1.3-mile underwater sewer line commenced in 2018 with the goal to improve wastewater conveyance.

The $46 million underground tunnel is the largest infrastructure project in Greenville’s history. Renewable Water Resources (ReWa), a ninety-seven-year-old organization that protects the region’s waterways and wastewater infrastructure, spearheaded the project. Black & Veatch led the design and provided construction management services. The project, known as the Reedy River Basin Sewer Tunnel or Dig Greenville, became operational earlier this year.

As ReWa Chief Executive Officer Joel Jones notes, “It’s a large area that has seen a good bit of growth. We expect it to continue and accelerate. This project will help facilitate and accommodate that growth, while also protecting against sewer overflows.”

CAPACITY PROBLEM

The existing sewer line in Greenville followed the Reedy River basin through the city’s downtown district. Near capacity, it faced pressure from Greenville’s recent and projected population growth. Without more capacity, the community would be at risk from increased overflows. That risk posed a direct threat to water quality, the environment and economic development.

ReWa considered eighteen alternatives before deciding on the gravity sewer tunnel. Rebuilding the sewer line was prohibitive, and too disruptive to the city and water basin. ReWa chose to install the new line underground, approximately 100 feet below the heart of the city.

The tunnel is 7 feet in diameter and virtually invisible to the public. Entry shafts at each end are the only hint of the massive pipe under the surface. The pipes are encased in granite, lined with fiberglass, and grouted. The gravity fed system means no mechanical equipment is needed to convey the flow of wastewater.

“While it is pricier to build, a deep sewer tunnel powered by gravity will be far less costly over its lifecycle for ReWa while providing the reliable additional capacity Greenville needed as it continues to grow,’’ Jones says.

DIG GREENVILLE

What:

Dig Greenville, also known as the Reedy River Basin Sewer Tunnel, is a 1.3-mile gravity-fed sewer line in South Carolina.

Project details:

The $46 million project started in 2018 and concluded in 2022. It is the largest infrastructure project in Greenville’s history. The project is expected to support Greenville’s wastewater conveyance needs for the next century.

Why it’s important:

The existing sewer line face pressure from increasing population. Without more capacity, the community would be at risk for overflow.

Digging deep:

The tunnel is located as far as 100 feet beneath the surface. Few people will even know it’s there. The only evidence visible are access points at each end. thirteen floor access doors manufactured by BILCO provide workers access to install, remove and repair equipment.

Did you know?

Greenville is sixth in population and growth rate in South Carolina.

LEND A HAND

One of the most challenging issues for the contractors emerged right at the outset.

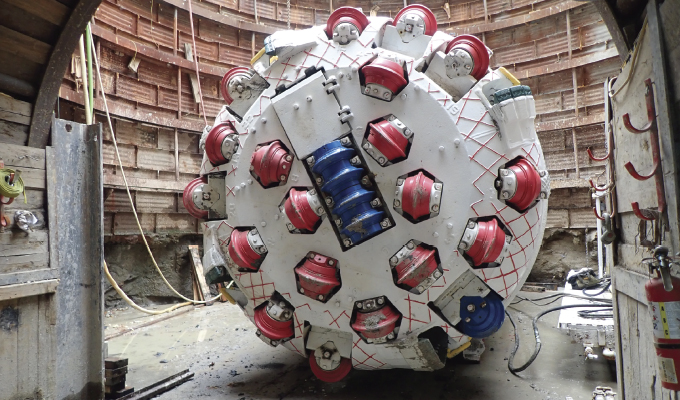

The initial plan was to drill from the downstream access shaft through the hard rock below with a tunnel boring machine. Before the TBM could be launched, however, a geotechnical investigation found the tunnel zone was comprised of soil and different types of rock in varying conditions.

“The tunnel boring machine can only work through one type of material,’’ Jones says. “Right when we were getting started, we saw that the granite was not where we thought it was.”

The complication resulted in hand-digging a starter tunnel. Starter tunnel construction also included drill and blast methods that required forty-one blasts over a nine-month period. Each blast was modified to fit the zone’s complex geology. Workers also fabricated and installed a customized steel shield to secure ground support for the 14-foot-round horseshoe-shaped starter tunnel.

“What we found was about 240 feet of clay and rock that we had to dig out,’’ Jones says. “It cost us about 10 months of project time. The tunnel boring machine can dig out about 40 to 50 feet per day. We were only digging out about two feet per day. It was very time-intensive and labor-intensive just to get started.”

The tunnel boring machine, known in the Greenville community as “Drilly”, carved out most of the tunnel. The 130-ton TBM, made by The Robbins Company in Canada, measures 249 feet and is one of only a handful of similar pieces of equipment in the world. Super Excavators of Wisconsin started tunnel digging in March 2018 and completed their work in September 2020.

“Once we got through digging the starter tunnel, we stayed on a fairly good track,’’ Jones says.

LIMITED VISIBILITY

For a project of this magnitude and duration, workers were surprisingly able to stay out of the public glare. Almost the entire construction was underground, and out of sight of city residents.

Teams constructed wooden fencing around the construction to minimize the aesthetic impact of the project. During a two-month winter period, one roadway was closed off to facilitate quicker construction for a sewer crossing across Richland Creek and to accommodate the city’s streambank restoration project.

While largely hidden from the public, the beginning and end points of the construction are identifiable by access doors.

The BILCO Company manufactured thirteen floor access doors of various sizes for the project. The doors allow access to vertical shafts—one is 35 feet deep, the other is 105 feet deep—in which workers will descend into the tunnel or lower equipment into the tunnel.

“We used those types of doors fairly often on our projects, especially at pump stations,’’ Jones says. “We find they have good durability and reliability.”

ON TIME, ON BUDGET

Cost overruns seem to impact every infrastructure project. The Greenville project, however, stayed within the confines of its original budget, and the delay in digging the starter tunnel was the only hiccup in otherwise well-executed project.

Now, city leaders in Greenville feel as though they have the wastewater infrastructure in place that can meet the community’s needs for the next century.

“This is a critical area in Greenville County,’’ Jones says. “The infrastructure serves a large area, and this tunnel will allow continued growth in the downtown area and northern parts of Greenville County. This project safely and efficiently revitalizes our wastewater infrastructure in the growing Greenville community for the next 100 years.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Thomas Renner writes on building, construction, engineering, and other trade industry topics for publications throughout the United States.

MODERN PUMPING TODAY, December 2022

Did you enjoy this article?

Subscribe to the FREE Digital Edition of Modern Pumping Today Magazine!